Background on model checking

See also

Model checking is the process of checking if a state machine abstract model of a system abides by certain correctness properties. These properties could include “don’t crash” or “don’t double-lock” (i.e., concurrency-related correctness).

To express this in mathematical logic, we use a temporal logic. The temporal is what clues us into the fact that this logic can handle transitions of a state machine over time. Under this temporal logic, the term for state machines is Kripke structures: a structure with different states, transitions between states, and predicates that hold at specific states. We say that a property

Notation similarity with axiomatic semantics

Compare this notation with the notation for axiomatic semantics, where for a given program state

and a formula , if holds under , then we can say: In general,

means that under model or assumption , holds.

Introduction

In the real world, we use model checking for software verification. How this works is you give the model checker your program in a language like C, where you might have potentially annotated error conditions or states (e.g., a branch that should be unreachable). The model checker then performs a few steps to verify a given correctness program for this program:

- Abstraction: builds an abstract model of the program as a state machine and a number of predicates that hold at different states in that machine.

- This is a kind of abstract interpretation!

- We do this to avoid exponential state blowup.

- When we say “predicates,” we mean predicates on program state:

, , etc. - One example of an abstraction is to ignore the values of all non-bool variables, and only add predicates that operate on bool variables!

- Verification: do the model checking. Can our state machine reach a state where our desired property doesn’t hold?

- Counterexample-driven refinement: if verification doesn’t succeed, we get back a counterexample showing where the state machine reaches a bad state. If this corresponds to an actual counterexample in our program, return that. Otherwise, our abstraction isn’t precise enough to prove program correctness, and we must refine our original abstraction.

But the first two steps are really slow! This paper proposes lazy abstraction: we iteratively build up our abstraction where needed, and when given a counterexample, only modify as much as is needed to rule out spurious counterexamples. If verification doesn’t succeed and we need to modify our model, we can incrementally refine the parts of the model that need work, rather than throwing out the whole model.

A locking example

In the paper, they go over the example of a program that revolves around a shared lock, like a Mutex or a shared resource. Double locking or unlocking is an error, which is annotated in the program. The actual program does some toy stuff to lock and unlock our lock.

int LOCK = 0;

lock() {

if (LOCK == 0) {

LOCK = 1;

} else {

// error

}

}

unlock() {

if (LOCK == 1) {

LOCK = 0;

} else {

// error

}

}

// Our example

main() {

if (???) {

do {

int got_lock = 0;

if (???) {

lock();

got_lock++;

}

if (got_lock) {

unlock();

}

} while (???);

}

do {

lock();

old = new;

if (???) {

unlock();

new++;

}

} while (new != old);

unlock();

}At a high level, the lazy abstraction algorithm proceeds in the following steps:

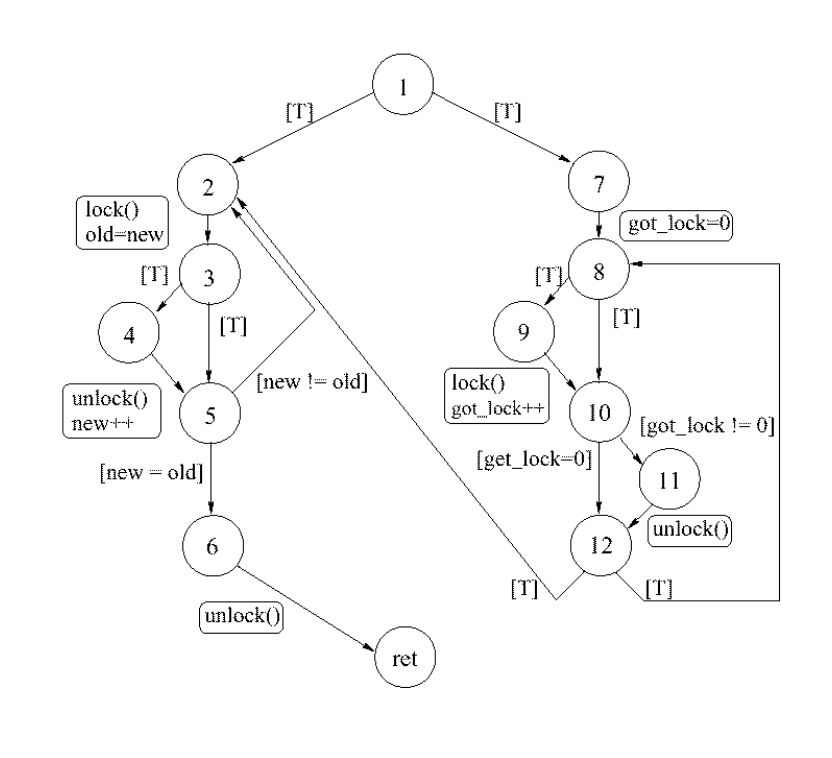

- Create the automata: edges are program statement(s) or a predicate branch taken, nodes contain a combination of predicates about the program state at that point. We can straightforwardly turn the CFG into a control flow automaton (CFA).

- At this point, we can also perform initial abstraction and choose a set of initial predicates; this set can be empty, meaning initially, each node contains no state information.

- e.g., our initial predicates could be

,

- e.g., our initial predicates could be

- And here’s a potential automata for the example above:

- At this point, we can also perform initial abstraction and choose a set of initial predicates; this set can be empty, meaning initially, each node contains no state information.

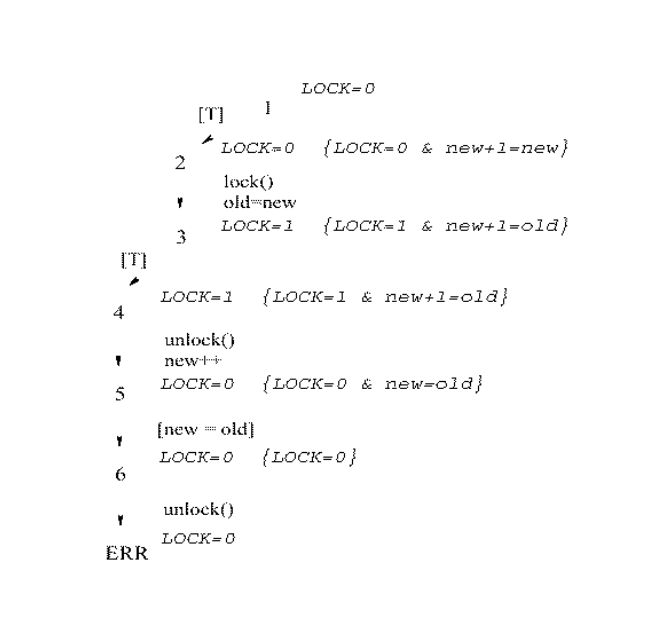

- Forward search: DFS through our automata, propagating abstract values (i.e., collecting predicates), until we hit an error state.

- Remember that nodes only record information about our abstracted predicates, nothing else! This is what we mean by abstraction.

- However, this information can be explicit conditional branches, or statements that modify values we care about in our predicates!

- i.e., assignment statements like

x = 1will modify any relevant predicates we have. We don’t just examine control conditions, but all statements! - e.g., moving through

unlock()should yieldas the predicate after.

- If we take a branch, we can’t record any information about the branch predicate unless it involves our abstract value predicates.

- These formulas are called reachable regions, representing the set of program states that reach this CFA node in terms of our abstracted predicates.

- Important: we don’t visit branches that we know to be false based on our predicates.

- If our current reachable region is

, and we encounter a predicate , the new reachable region is , so we don’t explore that.

- If our current reachable region is

- Remember that nodes only record information about our abstracted predicates, nothing else! This is what we mean by abstraction.

- Backwards counterexample analysis: if we hit an error node, we now move backwards to the root to see if this is a genuine counterexample trace, or a result of our abstraction being too coarse.

- For each node, we compute the bad region: the set of program states that can get to the error node from their corresponding place in the CFA.

- At each node on the path to the error, the bad region is the weakest precondition of

truewith respect to the statements from that node to the error node.- Basically: what is the minimum set of conditions to get from this node to the error node?

- Let’s break this down further.

- At the error node, the bad region is

true—every program state reaches the error state at this node. - If we go backwards through a conditional branch, we add the branch predicate to the new bad region if this adds any information to our bad region.

- If our old bad region had

, and the branch predicate is , we don’t need to add that to our bad region! This is why we have the weakest precondition thing. - Note that we always add branch predicates if they are information generative, regardless of what is in our abstraction predicates!

- If our old bad region had

- If we go backwards through some state modification/assignment, we modify any relevant predicates in our new bad region.

- If our bad region had

, and the statement is x += 1, we should now have, i.e., since before had a value one less than it did after the statement.

- If our bad region had

- Similar to forward propagation!

- At each node on the path to the error, the bad region is the weakest precondition of

- At each point, check if the conjunction of the reachable and bad regions is UNSAT.

- If this never happens, we’ve found a genuine counterexample.

- If this does, this means this path actually isn’t reachable from this node! This node is now the pivot node, where we’ll resume forward computation later on.

- We ask the theorem solver to tell us which clause is important to the proof of UNSAT. We should should add this predicate to our abstraction (i.e., track if it’s true or false), since this will give us additional information that will rule out certain branches from being executed.

- Not tracking this clause made us assume we’d visit an error node.

- If we track this clause, this will tell us information that might prevent us from visiting an error node—maybe the error node clause always returns

false! - In the text example, eventually we generate a clause

, which is always UNSAT.

- The theorem solver tells us the assumption of

between is important; this is what creates the UNSAT. - As a result, we should now be tracking if

or , since once we do that, we know that some branches might never be taken! - We know not to take this branch since we’re tracking this predicate and it’ll return

false!

- For each node, we compute the bad region: the set of program states that can get to the error node from their corresponding place in the CFA.

- Search with new predicates: Restart the forward pass at the pivot node while also including the relevant predicate above. This is called refining the model.

- If we see a previously visited state, stop the pass there and go to another branch!

- We do have to re-explore everything in the subtree up to the pivot node tho?

Formalism

TODO

I’ve skimmed the formalism. I haven’t fully internalized it. Maybe come back to this on a second pass.